I am presently trawling the archives of the Stornoway Gazette, looking for tributes to men who fell in the service of King and country during the First World War. The Gazette was not published until January 1917, meaning that the first half of the Great War was not covered. The tributes are incorporated into my WW1 tribute site "Faces from the Lewis War Memorial" (link leads to page with links to tributes).

Apart from that, I have also come across a tragic accident, in which a sailor was killed on board his ship. The Gazette reported on 4 May 1917 that the Norwegian barque Yuba had been brought in for inspection. The captain reported that he had found one of his seaman lying dead on the deck. He had gone up the rigging in the dark, and had evidently fallen from aloft. The remains were buried at Sandwick Cemetery.

I intend to visit Sandwick Cemetery to find that sailor's grave, and have also found out that the Yuba did not outlive its unfortunate crewmember for very long. German U boat U-50 torpedoed the sailing ship some five weeks later, on 7 June 1917, 110 miles north of Stornoway. The ship was reported to have been en route from Savannah (Georgia, USA) to Aarhus (Denmark). No lives were lost in the attack. The U-boat was destroyed by a mine off the Dutch island of Terschelling on 31 August 1917, with the loss of all hands.

Wednesday, 29 September 2010

Tuesday, 7 September 2010

Napier Commission in Skye - Attitude

I am currently working my way through the Napier Commission's Report for the Isle of Skye. The landowner at the time (1883) in the northwest of the island was Dr Nicol Martin. His attitude towards his tenantry is eloquently portrayed in reply to:

7570. You think they could not pay the rent?

—I know they could not do it, and they would not do it. They are getting indolent and lazy besides. Look at this winter; they did nothing but go about with fires on every hill, and playing sentinels to watch for fear of sheriff's officers coming with warnings to take their cattle for rent. They went about with pitch-forks and scythes and poles pointed with iron or steel, and it was a mercy no one would serve the processes upon them, or they would have murdered him sure enough. You cannot get a sheriffs officer now to serve a process on any tenant in Skye.

7570. You think they could not pay the rent?

—I know they could not do it, and they would not do it. They are getting indolent and lazy besides. Look at this winter; they did nothing but go about with fires on every hill, and playing sentinels to watch for fear of sheriff's officers coming with warnings to take their cattle for rent. They went about with pitch-forks and scythes and poles pointed with iron or steel, and it was a mercy no one would serve the processes upon them, or they would have murdered him sure enough. You cannot get a sheriffs officer now to serve a process on any tenant in Skye.

Raasay weeps

A harrowing tale of evictions from the island of Raasay, as I continue to copy, paste and clean up the findings of the Napier Commission, now sitting at Torran in Raasay. Raasay is the longish island off the east coast of Skye. Donald Mcleod, a 78-year old former fisherman from Rona, just north of Raasay, tells of the evictions of fourteen townships. Chairman Lord Napier is asking about this.

7837. We want to find out if you know about the evictions in former times. The first one began in the time of M'Leod himself about forty years ago. Do you recollect that?

—I don't remember the first removing, but I remember Mr Rainy about thirty years ago clearing fourteen townships, and he made them into a sheep farm which he had in his own hands.

7838. What became of the people?

—They went to other kingdoms—some to America, some to Australia, and other places that they could think of. Mr Rainy enacted a rule that no one should marry in the island. There was one man there who married in spite of him, and because he did so, he put him out of his father's house, and that man went to a bothy—to a sheep cot. Mr Rainy then came and demolished the sheep cot upon him, and extinguished his fire, and neither friend nor any one else dared give him a night's shelter. He was not allowed entrance into any house.

7839. What was his name?

—John MLeod.

7840. What is the name of the town were his father was?

—Arnish.

7841. Will you give us a rough estimate of the population of the fourteen townships?

—I cannot; there were a great number of people.

7842. Were they hundreds?

—Yes, hundreds, young and old. I am sure there were about one hundred in each of two townships.

7843. Will you name the towns?

—Castle, Screpidale, two Hallaigs, Ceancnock, Leachd, two Fearns, Eyre, Suisinish, Doirredomhain, Mainish.

[...]

7858. Did the people out of these fourteen townships that Rainy cleared go of their own accord?

—No, not at all. The people were very sorry to leave at that time. They were weeping and wailing and lamenting. They were taking handfuls of grass that was growing over the graves of their families in the churchyard, as remembrances of their kindred.

7859. Mr Cameron.

—Might that not occur even though the people left of their own free-will, if they were much attached to their kindred?

—No, they were sent away against their will, in spite of them.

7837. We want to find out if you know about the evictions in former times. The first one began in the time of M'Leod himself about forty years ago. Do you recollect that?

—I don't remember the first removing, but I remember Mr Rainy about thirty years ago clearing fourteen townships, and he made them into a sheep farm which he had in his own hands.

7838. What became of the people?

—They went to other kingdoms—some to America, some to Australia, and other places that they could think of. Mr Rainy enacted a rule that no one should marry in the island. There was one man there who married in spite of him, and because he did so, he put him out of his father's house, and that man went to a bothy—to a sheep cot. Mr Rainy then came and demolished the sheep cot upon him, and extinguished his fire, and neither friend nor any one else dared give him a night's shelter. He was not allowed entrance into any house.

7839. What was his name?

—John MLeod.

7840. What is the name of the town were his father was?

—Arnish.

7841. Will you give us a rough estimate of the population of the fourteen townships?

—I cannot; there were a great number of people.

7842. Were they hundreds?

—Yes, hundreds, young and old. I am sure there were about one hundred in each of two townships.

7843. Will you name the towns?

—Castle, Screpidale, two Hallaigs, Ceancnock, Leachd, two Fearns, Eyre, Suisinish, Doirredomhain, Mainish.

[...]

7858. Did the people out of these fourteen townships that Rainy cleared go of their own accord?

—No, not at all. The people were very sorry to leave at that time. They were weeping and wailing and lamenting. They were taking handfuls of grass that was growing over the graves of their families in the churchyard, as remembrances of their kindred.

7859. Mr Cameron.

—Might that not occur even though the people left of their own free-will, if they were much attached to their kindred?

—No, they were sent away against their will, in spite of them.

Thursday, 2 September 2010

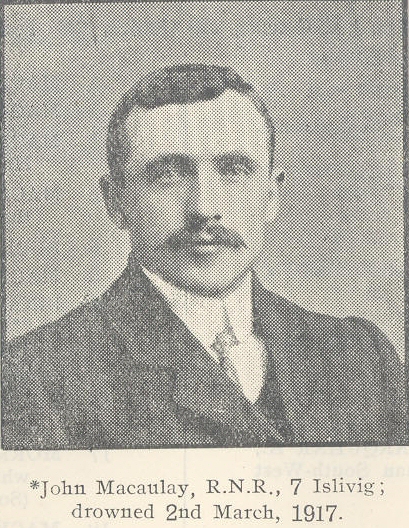

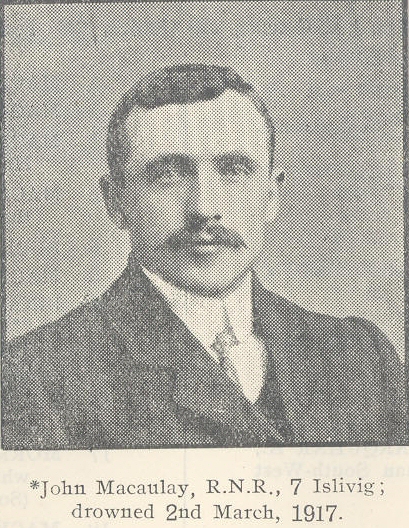

John Macaulay, 7 Islivig

A tribute and account of the fate of Leading Deckhand John Macaulay.

Please note that further research into John, his ship and shipmates is relayed on this site.

John Macaulay was lost when SS Kenmare was torpedoed in the Irish Sea on Saturday, 2 March 1918. He came from the village of Islivig in the district of Uig in Lewis. His remains turned up on the east coast of Ireland, north of Dublin, and lie buried in a grave in Balrothery. His grave is marked by a Commonwealth War¬graves Commission headstone.

John Macaulay was lost when SS Kenmare was torpedoed in the Irish Sea on Saturday, 2 March 1918. He came from the village of Islivig in the district of Uig in Lewis. His remains turned up on the east coast of Ireland, north of Dublin, and lie buried in a grave in Balrothery. His grave is marked by a Commonwealth War¬graves Commission headstone.

This tribute is dedicated to his memory, and endeavours to tell the story of SS Kenmare, the German submarine U-104 which fired the fatal torpedo and John Macaulay’s final resting place.

John’s family history

John was the son of fisherman Donald Macaulay of Islivig and domestic servant Margaret Macaulay who were married at Miavaig on 4 April 1878. Both were aged 26 at the time. It is worth pointing out that in the Gaelic community, the name Margaret is sometimes converted to Peggy. They continued to live in Islivig after their marriage. Donald and Peggy were blessed with the birth of a son, John, on 7 December 1881. It has not been part of my investigations to find out whether they had any more children.

Thirty-six years later, on 16 January 1917, John (now living at 7 Islivig) was married to Catherine Ann Macaulay, a 29-year old nurse from 19 Brenish. She is the daughter of boat-builder John Macaulay and Isabella Matheson. The marriage was conducted at Seaforth House on Scotland Street in Stornoway.

By that time, John’s mother Peggy had died, and Donald, by that time aged 62, was a crofter. His son, John, was a seaman in the Merchant Service, but (1917 being a war year) also marked as being in the Royal Naval Reserve, as so many islanders were.

S.S. Kenmare

The Kenmare was launched on 16 February 1895 at Wigham, Richardson and Co. of Newcastle upon Tyne. She was powered by a triple-expansion steam engine, generating 437 hp. She was completed for the City of Cork Steam Packet Co. Ltd. Her dimensions were 264.5 x 36.5 x 16.9 feet, measuring 1,346 gross tons.

During the First World War, she found herself under attack by German submarines (U-boats) on four occasions. On 27 June 1915, SS Kenmare was attacked by gunfire off Youghall, but outran her attacker with minimal damage. Two years later, on 21 October 1917, Kenmare was off Holyhead, bound from Liverpool to Cork, when a torpedo passed only a few feet from her stern. A few weeks later, the Kenmare had to fire at a submarine that was chasing her. However, the last attack, on 2 March 1918, proved fatal.

That day, SS Kenmare was sailing from Liverpool to Cork with a general cargo at position 53°40’095”N 5°06’099”W. This is 60 km (approximately 35 nautical miles) north of east from Skerries, Co Dublin and 40kms (approximately 25 nautical miles) north west from The Skerries, Anglesey.. At around 7pm, U-104 fired a torpedo without warning. It inflicted severe damage, and Kenmare sank by the stern within two minutes. Only one lifeboat was serviceable, and the three who had managed to get into it tried to find other crew members. Three more were saved. In spite of shouting being heard, the occupants of the lifeboat did not manage to locate these unfortunates as it was dark by that time and the sea covered in wreckage. Twenty-nine members of crew perished, 24 of whom were in a boat which overturned – the weather being poor and the sea rough at the time. The First Mate, four crewmen and Gunner James Henry Chamberlain Brougham RNVR, aged 20 survived the torpedoing of the ship. This was remarkable, bearing in mind that the ship sank in just two minutes. Two other gunners, Able Seaman Albert Edward Aston RNVR and Leading Deck Hand John Macaulay RNR did not survive. Apparently, the ship’s gun had been thrown from its mountings by the force of the explosion. The survivors were picked up by the steamer Glenside the next morning, and taken to Dublin.

U-boat postscript

U-boat 104 had been in service for only five months at the time of the attack on the Kenmare. U-104 sank a total of eight ships, which accounted for a third of the number of ships (25) sunk by its commander, 32-year old Kapitän-Leutnant zur See Kurt Bernis, until he was killed in the sinking of his U-boat on 25 April 1918.

On 23 April 1918, U-104 was attacked by USS Cushing using depth charges. These damaged the submarine. Two days later, HMS Jessamine came across the submarine on the surface in St George’s Channel as its crew were attempting to repair the damage, caused by the depth charges. KLt Bernis dived his submarine, but depth charges from HMS Jessamine forced him to surface. The U-boat was finally sunk, taking 31 to the bottom with her. Ten sailors were left in the water, after their vessel went down, of whom only one was picked up by the warship. The other nine were left to drown in the sea.

Found in Ireland

John Macaulay was not saved from the sinking of the Kenmare. Although the one working lifeboat remained on the scene as long as possible, the shouting of the floundering seamen ceased after some 10 minutes. It is a matter of conjecture what happened during the next fourteen days.

Coast Watchman John Doherty and Constable Masterson found the body of John Macaulay on a beach at King’s Point (shown left) north of Balbriggan Co. Dublin on Saturday 16th March 1918. Two other bodies of sailors were found on the same day washed up on nearby beaches at Skerries Co. Dublin and Gormanston Co. Meath, but only John Macaulay’s body could be identified. He carried a letter which is said to have identified him as George [sic] Mcauley of Stornaway. He is described as a fine young sailor of about 25 – however, at the time of his death, John Macaulay was actually aged thirty-five. All three were dressed in semi-naval uniform.

Coast Watchman John Doherty and Constable Masterson found the body of John Macaulay on a beach at King’s Point (shown left) north of Balbriggan Co. Dublin on Saturday 16th March 1918. Two other bodies of sailors were found on the same day washed up on nearby beaches at Skerries Co. Dublin and Gormanston Co. Meath, but only John Macaulay’s body could be identified. He carried a letter which is said to have identified him as George [sic] Mcauley of Stornaway. He is described as a fine young sailor of about 25 – however, at the time of his death, John Macaulay was actually aged thirty-five. All three were dressed in semi-naval uniform.

Inquests into the deaths of the three sailors were held by Coroners Friery and Corry, and the evidence disclosed nothing further than that two of the men carried beads and scapulars, while a disc showed that McAuley was a Presbyterian. The bodies, which were only a few days in the water, bore no sign of violence, and the medical testimony was that death was due to drowning. A verdict of “found drowned” was duly returned by the Jury under foreman Mr George Mongey.

News found its way to John’s native Isle of Lewis, and was relayed by local weekly newspaper Stornoway Gazette, on 15 March 1918.

“It is with deep regret we have to record the death by drowning of Seaman John Macaulay (Iain Dhomhnaill an Taillear) [John the son of Donald the Tailor] Islivig on Saturday 2nd inst. His boat the “Kenmore” [sic] was torpedoed, and only six out of a crew of thirty-five were saved. John was one of the finest young men that could be met in a day’s march. To his young and sorrowing widow, and to his other near relatives and friends, the heartfelt sympathy of the whole community is extended in their very sad and sore bereavement.”

John’s family had endeavoured to have the body transferred home, but the authorities would not sanction this. An account of the funeral was forwarded to his family by the Acting Divisional Officer of Coastguard at Rush, and the Stornoway Gazette copies this; I insert additional information as supplied by the Drogheda Independent and Drogheda Advertiser in their editions of March 23rd, 1918.

The funeral started from the Coastguard Station, Balbriggan (shown left, about 1920). The military supplied four horses and the coffin was place on the limber, and we marched through the town of Balbriggan. The military firing party, with a piper at its head, led the procession; a military funeral party and a body of police followed behind the coffin with as many of the Coastguard as could be obtained; and a large crowd of the inhabitants followed to the churchyard. the piper played a lament and other Scottish airs suitable for the occasion. (Pipers’ Band of the Royal Engineers playing the Dead March) The military also took photographs of the funeral and if they turn out successful you will be sent copies. Your son is buried at Balrothery Churchyard, and the funeral service was carried out by the Protestant minister (Rev. H. B. Good, Rector, Rev. C. Benson L.L.D. and Rev. R. Scriven). Your son was given the grandest funeral that was ever seen in Balbriggan and I think it is particularly gratifying to know that full honours were paid to his remains. Three volleys were fired over the grave and the piper played between each volley.”

Postscript

It would stand to reason that such a grand occasion would be remembered for many years to come in a small town like Balbriggan. Not in this instance. British armed forces burned and looted the centre of the town on 9 September 1920 in reprisal for the alleged killing of an R.I.C officer by the I.R.A. earlier in the evening, as the unfortunate policeman left a local pub. This would have eclipsed if not erased the burial in the collective and popular memory of the inhabitants of the town.

In the 1930s, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission commissioned the erection of a grave-stone over John Macaulay’s grave at Balrothery, a gravestone which faces east. His was one of many such gravestones in Ireland that were put up by the Office of Public Works, a branch of the Irish Government. In the 1920s, the family ordered the installation of iron railings around the grave site. The spelling of John Macaulay’s name on the gravestone (Macauley) is noted, but the information on the stone confirms the identity of the casualty.

Catherine Ann, John’s wife, died in Stornoway on 17 April 1961, aged 73. From the limited resources available to me, I have not been able to find out if she remarried and / or had children.

John’s father, Donald Macaulay, passed away in the district of Uig in 1933, aged 80.

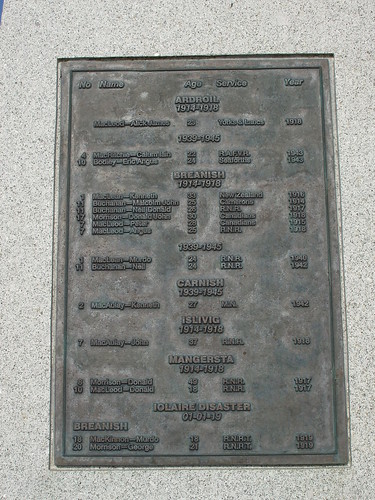

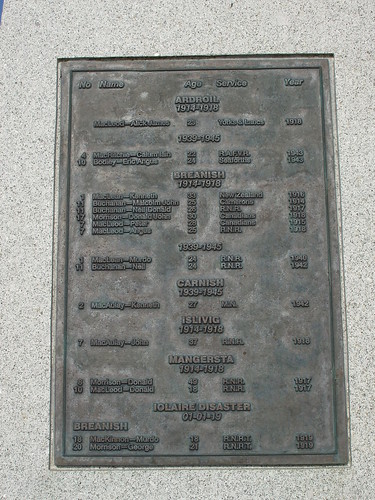

John Macaulay is also remembered on the commemorative panel in Grangegorman Military Cemetery, Blackhorse Avenue, Dublin.

He is also mentioned on the West Uig division of the Lewis War Memorial at Stornoway

and on the Uig War Memorial at Timsgarry

Sources

• David J. Grundy, Skerries, Dublin

• Scotland’s People

• The Drogheda Historical Society, from the archives of The Drogheda Independent and The Drogheda Advertiser, Mellmount Museum, Drogheda, Co Louth, Ireland

• Stornoway Gazette, 15th March 1918 and 12th April 1918, from transcript of original copies, held on microfiche at Stornoway Library

• Comann Eachdraidh Uig, Uig Museum, Timsgarry, Isle of Lewis

• Commonwealth War Graves Commission

• Cork Examiner archives (now Irish Examiner), courtesy Brendan Mooney

• From book: The Irish Boats (Cork & Waterford), courtesy Brendan Mooney

• Uboat.net

• Portrait photograph: Loyal Lewis Roll of Honour 1914-1918, Stornoway Gazette, 1921 (held at Stornoway Library)

• Photographs of Balbriggan Coast Guard Station are the copyright of Mr. David Brangan and is reproduced with his kind permission.

Please note that further research into John, his ship and shipmates is relayed on this site.

John Macaulay was lost when SS Kenmare was torpedoed in the Irish Sea on Saturday, 2 March 1918. He came from the village of Islivig in the district of Uig in Lewis. His remains turned up on the east coast of Ireland, north of Dublin, and lie buried in a grave in Balrothery. His grave is marked by a Commonwealth War¬graves Commission headstone.

John Macaulay was lost when SS Kenmare was torpedoed in the Irish Sea on Saturday, 2 March 1918. He came from the village of Islivig in the district of Uig in Lewis. His remains turned up on the east coast of Ireland, north of Dublin, and lie buried in a grave in Balrothery. His grave is marked by a Commonwealth War¬graves Commission headstone. This tribute is dedicated to his memory, and endeavours to tell the story of SS Kenmare, the German submarine U-104 which fired the fatal torpedo and John Macaulay’s final resting place.

John’s family history

John was the son of fisherman Donald Macaulay of Islivig and domestic servant Margaret Macaulay who were married at Miavaig on 4 April 1878. Both were aged 26 at the time. It is worth pointing out that in the Gaelic community, the name Margaret is sometimes converted to Peggy. They continued to live in Islivig after their marriage. Donald and Peggy were blessed with the birth of a son, John, on 7 December 1881. It has not been part of my investigations to find out whether they had any more children.

Thirty-six years later, on 16 January 1917, John (now living at 7 Islivig) was married to Catherine Ann Macaulay, a 29-year old nurse from 19 Brenish. She is the daughter of boat-builder John Macaulay and Isabella Matheson. The marriage was conducted at Seaforth House on Scotland Street in Stornoway.

By that time, John’s mother Peggy had died, and Donald, by that time aged 62, was a crofter. His son, John, was a seaman in the Merchant Service, but (1917 being a war year) also marked as being in the Royal Naval Reserve, as so many islanders were.

S.S. Kenmare

The Kenmare was launched on 16 February 1895 at Wigham, Richardson and Co. of Newcastle upon Tyne. She was powered by a triple-expansion steam engine, generating 437 hp. She was completed for the City of Cork Steam Packet Co. Ltd. Her dimensions were 264.5 x 36.5 x 16.9 feet, measuring 1,346 gross tons.

During the First World War, she found herself under attack by German submarines (U-boats) on four occasions. On 27 June 1915, SS Kenmare was attacked by gunfire off Youghall, but outran her attacker with minimal damage. Two years later, on 21 October 1917, Kenmare was off Holyhead, bound from Liverpool to Cork, when a torpedo passed only a few feet from her stern. A few weeks later, the Kenmare had to fire at a submarine that was chasing her. However, the last attack, on 2 March 1918, proved fatal.

That day, SS Kenmare was sailing from Liverpool to Cork with a general cargo at position 53°40’095”N 5°06’099”W. This is 60 km (approximately 35 nautical miles) north of east from Skerries, Co Dublin and 40kms (approximately 25 nautical miles) north west from The Skerries, Anglesey.. At around 7pm, U-104 fired a torpedo without warning. It inflicted severe damage, and Kenmare sank by the stern within two minutes. Only one lifeboat was serviceable, and the three who had managed to get into it tried to find other crew members. Three more were saved. In spite of shouting being heard, the occupants of the lifeboat did not manage to locate these unfortunates as it was dark by that time and the sea covered in wreckage. Twenty-nine members of crew perished, 24 of whom were in a boat which overturned – the weather being poor and the sea rough at the time. The First Mate, four crewmen and Gunner James Henry Chamberlain Brougham RNVR, aged 20 survived the torpedoing of the ship. This was remarkable, bearing in mind that the ship sank in just two minutes. Two other gunners, Able Seaman Albert Edward Aston RNVR and Leading Deck Hand John Macaulay RNR did not survive. Apparently, the ship’s gun had been thrown from its mountings by the force of the explosion. The survivors were picked up by the steamer Glenside the next morning, and taken to Dublin.

U-boat postscript

U-boat 104 had been in service for only five months at the time of the attack on the Kenmare. U-104 sank a total of eight ships, which accounted for a third of the number of ships (25) sunk by its commander, 32-year old Kapitän-Leutnant zur See Kurt Bernis, until he was killed in the sinking of his U-boat on 25 April 1918.

On 23 April 1918, U-104 was attacked by USS Cushing using depth charges. These damaged the submarine. Two days later, HMS Jessamine came across the submarine on the surface in St George’s Channel as its crew were attempting to repair the damage, caused by the depth charges. KLt Bernis dived his submarine, but depth charges from HMS Jessamine forced him to surface. The U-boat was finally sunk, taking 31 to the bottom with her. Ten sailors were left in the water, after their vessel went down, of whom only one was picked up by the warship. The other nine were left to drown in the sea.

Found in Ireland

John Macaulay was not saved from the sinking of the Kenmare. Although the one working lifeboat remained on the scene as long as possible, the shouting of the floundering seamen ceased after some 10 minutes. It is a matter of conjecture what happened during the next fourteen days.

Coast Watchman John Doherty and Constable Masterson found the body of John Macaulay on a beach at King’s Point (shown left) north of Balbriggan Co. Dublin on Saturday 16th March 1918. Two other bodies of sailors were found on the same day washed up on nearby beaches at Skerries Co. Dublin and Gormanston Co. Meath, but only John Macaulay’s body could be identified. He carried a letter which is said to have identified him as George [sic] Mcauley of Stornaway. He is described as a fine young sailor of about 25 – however, at the time of his death, John Macaulay was actually aged thirty-five. All three were dressed in semi-naval uniform.

Coast Watchman John Doherty and Constable Masterson found the body of John Macaulay on a beach at King’s Point (shown left) north of Balbriggan Co. Dublin on Saturday 16th March 1918. Two other bodies of sailors were found on the same day washed up on nearby beaches at Skerries Co. Dublin and Gormanston Co. Meath, but only John Macaulay’s body could be identified. He carried a letter which is said to have identified him as George [sic] Mcauley of Stornaway. He is described as a fine young sailor of about 25 – however, at the time of his death, John Macaulay was actually aged thirty-five. All three were dressed in semi-naval uniform. Inquests into the deaths of the three sailors were held by Coroners Friery and Corry, and the evidence disclosed nothing further than that two of the men carried beads and scapulars, while a disc showed that McAuley was a Presbyterian. The bodies, which were only a few days in the water, bore no sign of violence, and the medical testimony was that death was due to drowning. A verdict of “found drowned” was duly returned by the Jury under foreman Mr George Mongey.

News found its way to John’s native Isle of Lewis, and was relayed by local weekly newspaper Stornoway Gazette, on 15 March 1918.

“It is with deep regret we have to record the death by drowning of Seaman John Macaulay (Iain Dhomhnaill an Taillear) [John the son of Donald the Tailor] Islivig on Saturday 2nd inst. His boat the “Kenmore” [sic] was torpedoed, and only six out of a crew of thirty-five were saved. John was one of the finest young men that could be met in a day’s march. To his young and sorrowing widow, and to his other near relatives and friends, the heartfelt sympathy of the whole community is extended in their very sad and sore bereavement.”

John’s family had endeavoured to have the body transferred home, but the authorities would not sanction this. An account of the funeral was forwarded to his family by the Acting Divisional Officer of Coastguard at Rush, and the Stornoway Gazette copies this; I insert additional information as supplied by the Drogheda Independent and Drogheda Advertiser in their editions of March 23rd, 1918.

The funeral started from the Coastguard Station, Balbriggan (shown left, about 1920). The military supplied four horses and the coffin was place on the limber, and we marched through the town of Balbriggan. The military firing party, with a piper at its head, led the procession; a military funeral party and a body of police followed behind the coffin with as many of the Coastguard as could be obtained; and a large crowd of the inhabitants followed to the churchyard. the piper played a lament and other Scottish airs suitable for the occasion. (Pipers’ Band of the Royal Engineers playing the Dead March) The military also took photographs of the funeral and if they turn out successful you will be sent copies. Your son is buried at Balrothery Churchyard, and the funeral service was carried out by the Protestant minister (Rev. H. B. Good, Rector, Rev. C. Benson L.L.D. and Rev. R. Scriven). Your son was given the grandest funeral that was ever seen in Balbriggan and I think it is particularly gratifying to know that full honours were paid to his remains. Three volleys were fired over the grave and the piper played between each volley.”

Postscript

It would stand to reason that such a grand occasion would be remembered for many years to come in a small town like Balbriggan. Not in this instance. British armed forces burned and looted the centre of the town on 9 September 1920 in reprisal for the alleged killing of an R.I.C officer by the I.R.A. earlier in the evening, as the unfortunate policeman left a local pub. This would have eclipsed if not erased the burial in the collective and popular memory of the inhabitants of the town.

In the 1930s, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission commissioned the erection of a grave-stone over John Macaulay’s grave at Balrothery, a gravestone which faces east. His was one of many such gravestones in Ireland that were put up by the Office of Public Works, a branch of the Irish Government. In the 1920s, the family ordered the installation of iron railings around the grave site. The spelling of John Macaulay’s name on the gravestone (Macauley) is noted, but the information on the stone confirms the identity of the casualty.

Catherine Ann, John’s wife, died in Stornoway on 17 April 1961, aged 73. From the limited resources available to me, I have not been able to find out if she remarried and / or had children.

John’s father, Donald Macaulay, passed away in the district of Uig in 1933, aged 80.

John Macaulay is also remembered on the commemorative panel in Grangegorman Military Cemetery, Blackhorse Avenue, Dublin.

He is also mentioned on the West Uig division of the Lewis War Memorial at Stornoway

and on the Uig War Memorial at Timsgarry

Sources

• David J. Grundy, Skerries, Dublin

• Scotland’s People

• The Drogheda Historical Society, from the archives of The Drogheda Independent and The Drogheda Advertiser, Mellmount Museum, Drogheda, Co Louth, Ireland

• Stornoway Gazette, 15th March 1918 and 12th April 1918, from transcript of original copies, held on microfiche at Stornoway Library

• Comann Eachdraidh Uig, Uig Museum, Timsgarry, Isle of Lewis

• Commonwealth War Graves Commission

• Cork Examiner archives (now Irish Examiner), courtesy Brendan Mooney

• From book: The Irish Boats (Cork & Waterford), courtesy Brendan Mooney

• Uboat.net

• Portrait photograph: Loyal Lewis Roll of Honour 1914-1918, Stornoway Gazette, 1921 (held at Stornoway Library)

• Photographs of Balbriggan Coast Guard Station are the copyright of Mr. David Brangan and is reproduced with his kind permission.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)